A paper published today in Communications Earth & Environment by Anthony J. I. Clarke and Christopher L. Kirkland provides one of the most robust detrital mineral provenance tests yet applied to the question of how Stonehenge’s non-sarsen megaliths reached Salisbury Plain. Using U–Pb dating of zircon and apatite from modern stream sediments, the authors present a compelling case that Pleistocene glacial transport is unlikely, reinforcing the prevailing view that Neolithic people moved the bluestones from Mynydd Preseli and the Altar Stone from northeast Scotland.

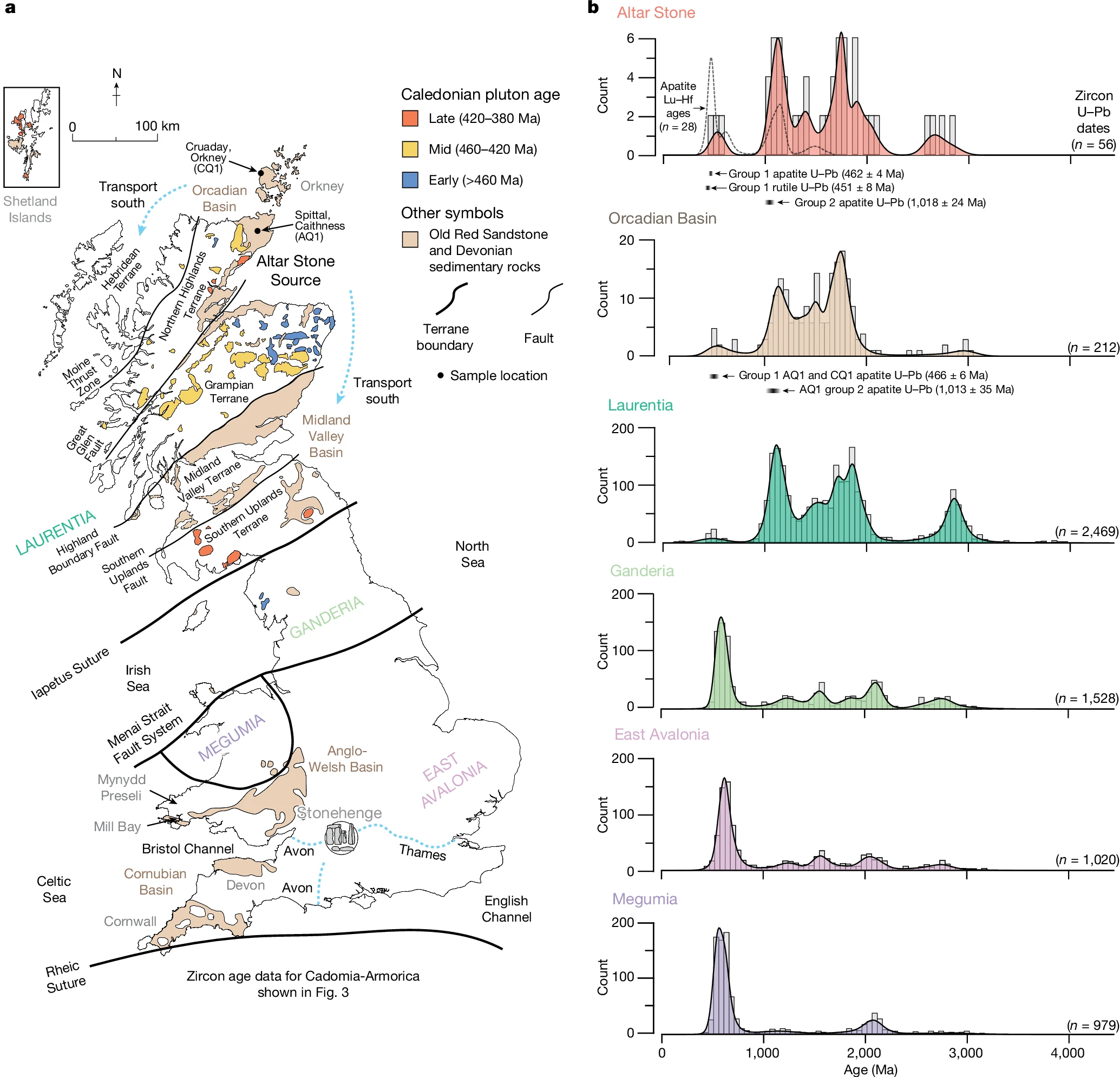

The study’s methodological rigour stands out. The authors collected four stream-sand samples (SH1–SH4) from the Avon–Test drainage system encircling Salisbury Plain, targeting catchments draining Chalk-dominated terrain with negligible local zircon sources. They analysed 550 zircon grains, yielding 401 concordant analyses (≤10% discordance), and 250 apatite grains. The zircon dataset is large by detrital geochronology standards, and the authors demonstrate inter-sample homogeneity via Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests, justifying aggregation into a composite spectrum. Age peaks at ca. 1090, 1690 and 1740 Ma dominate, matching Laurentian basement terranes of northern Britain (Grenville, Penokean, Trans-Hudson) rather than the Cadomian, Avalonian or Megumian signatures expected from southern Britain or Wales. The near-absence of Phanerozoic grains (only 8%) and the lack of a prominent Darriwilian (ca. 464 Ma) population—diagnostic of Mynydd Preseli rhyolites—are particularly telling. A single 464 ± 16 Ma grain from the Wylye catchment is interpreted as an inevitable outlier in a large-n dataset, most plausibly recycled from Palaeogene units rather than delivered directly from Wales.

Apatite U–Pb data add a second, independent constraint. Tera-Wasserburg regressions and ²⁰⁷Pb-corrected ages converge on a ca. 60–65 Ma signal, interpreted as post-depositional resetting linked to distal Alpine orogeny effects. Grain morphology (anhedral, abraded, homogeneous CL response) points to derivation from mature sedimentary or diagenetic sources, consistent with reworking of Palaeogene cover sequences rather than first-cycle crystalline input.

Statistical and visual comparisons strengthen the interpretation. A multidimensional scaling plot positions the Salisbury Plain composite close to the Thanet Formation (early Palaeocene, London Basin), statistically indistinguishable by KS test, and distant from potential glacial source regions. The authors argue that Neogene erosion of Palaeogene strata (including the Thanet Formation and Clay-with-Flints) released durable Laurentian zircons onto the zircon-poor Chalk, where they were subsequently recycled into modern river sands via ancestral Avon and Wylye drainage. This polycyclic pathway explains the observed fingerprint without invoking ice-sheet transport.

The work directly addresses the glacial hypothesis’s key prediction: that southward ice flow from the Midlands or southwest from Wales would have delivered a detectable ca. 464 Ma zircon signal and Laurentian signatures from northern Britain. Neither is present in meaningful abundance. The authors also note the absence of coarse first-cycle lithic clasts or undisputed glacial indicators (tills, erratics) on the Plain, aligning with the consensus that Anglian ice margins lay well to the north.

Overall, the study is methodologically sound, with a large, well-characterised dataset, appropriate statistical treatment, and integration of multiple mineral systems and comparative datasets. It does not definitively disprove glacial transport—absence of evidence is not evidence of absence—but it significantly weakens the hypothesis by showing that the modern detrital cargo is inconsistent with substantial glaciogenic input. For those working on Stonehenge provenance, this paper represents a high bar for future tests of the glacial model and tilts the balance further toward human agency.